There’s a problem with many of our political systems at the moment. Or, more specifically, the way our policy is put together. Think tank’s are assembled, productivity inquiries commissioned and research is gathered to guide the policies that are created to make our nation stronger. Makes sense, doesn’t it?

Unfortunately, what doesn’t make sense is how research and expert advice is being continually overlooked when it comes time to actually create the policy.

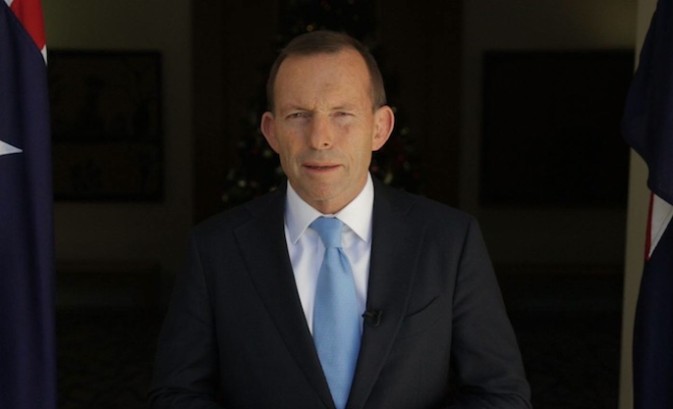

One of the clear examples of this is in Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s approach to early education and care since his election. Not only has he hit pause on some key quality drivers in the National Quality Framework (specifically around educator qualifications and staff-to-child ratios), we’re now seeing hints that Australian Government funding for preschool education is set to be scaled back.

Mr Abbott has made it clear that his paid parental scheme is the best way forward for parents with children, despite the Commission of Audit calling the proposed scheme excessive.

Sure, getting women back into the workforce certainly makes good fiscal sense, which is what the PPL scheme is hyped to do, but there’s some pretty clear expert advice that suggests that’s all it is, hype.

Clear evidence, though, shows that directing funding towards the provision of quality education and care will lead to better outcomes for children. This will serve them well into the future, and reduce the impact on our welfare, prison and even health systems. The government need look no further than Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman’s research if they need proof.

Speaking of research, there’s plenty of it, from here and abroad, that says the most important years for brain development happen between birth to five years, which is why it so important that quality education and care is delivered during this period, not just in the preschool years. The key is “quality”, and you don’t get that without investment or by maintaining quality reforms. According to comparisons between OECD countries, we rank pretty low in the numbers of children enrolled in early education, particularly among preschoolers. We also spend 0.6% of our GDP on early education (the OECD minimum recommendation is 1.0%).

If Mr Abbott is truly serious about being “fair dinkum” in his support of Australian working families, then he should recognise the true value of early education and direct more funding to the sector, not pare it back. Because, let’s face it, when those women are ready to return to work, they’ll be needing quality early education and care for their children.

Until our policies and investment reflect the importance of the sector, its role in children’s lives and outcomes, and the important role of the sector’s (largely female) workforce, any claims that we’re being either fair or dinkum just don’t ring true.

Other policies coming up short?

- Alcohol-related violence: Crikey‘s politics editor, Bernard Keane, attests that research was given a back seat when it came to Sydney’s new alcohol-related violence policies developed by Premier Barry O’Farrell. In his article, Keane suggests Premier O’Farrell, who’d previously brought up research indicating declining levels of violence on Sydney’s streets, was forced to ignore research because public perception of the issue had been influenced by Sydney’s major newspapers, in a “shameless” campaign of misrepresentation.

- Climate change: despite irrefutable evidence supporting the effects of climate change, the Australian Government has wound back policies (and eradicated departments) set up by previous governments. Australia’s action on climate change, which had previously been described as pioneering, has drawn world-wide criticism. After PM Tony Abbott’s removal of climate change off this year’s G20 agenda, European Union officials claim Australia has become “disengaged” on the climate change issue, and described the change in focus of this government as “losing an ally“.

No Comments Yet